A battle has erupted over the last will of author Colleen McCullough, with the widower accused of manipulating his ill wife to secure her fortune, according to court documents filed in the NSW Supreme Court.

A will, effectively revoking an earlier bequest to the University of Oklahoma Foundation, was signed by Dr McCullough at her home 12 days before she died in a Norfolk Island hospital from a series of strokes.

But the late author’s friend and executor, Selwa Anthony, the plaintiff in a legal battle to be heard over five days by the court from May 22, has challenged the will’s validity claiming it was signed by Dr McCullough in ”suspicious circumstances”. The battle will now focus on which was the author’s valid last will.

Dr McCullough was ”substantially bedridden”, unable to make or receive phone calls, had advanced macular degeneration which caused ”severe vision impairment” and was ”not capable of reading the document” she allegedly signed, Ms Anthony said in pleadings filed to the court.

The author’s husband, Mr Robinson, has been accused of taking advantage of his late wife’s ”poor health, isolation, fatigue and dependence of the deceased, so as to dominate, overbear and overburden her”. He is accused of forcing his wife to change her last will so that he will inherit her entire estate. In his defence, Mr Robinson claims he is the rightful sole beneficiary of his wife’s estate and the 2015 will was prepared properly at the instruction of his late wife. McCullough and Mr Robinson were married for 30 years.

The author’s husband, Mr Robinson, has been accused of taking advantage of his late wife’s ”poor health, isolation, fatigue and dependence of the deceased, so as to dominate, overbear and overburden her”. He is accused of forcing his wife to change her last will so that he will inherit her entire estate. In his defence, Mr Robinson claims he is the rightful sole beneficiary of his wife’s estate and the 2015 will was prepared properly at the instruction of his late wife. McCullough and Mr Robinson were married for 30 years.

He alleges Ms Anthony had failed to prove an earlier will made out in Sydney in 2014 which names the university as beneficiary. Mr Robinson also claims that a document subsequently deposited in the Supreme Court in July 2015 propounding to be this will is a ”forgery fabricated by a person or persons unknown”. Further, it was not Dr McCullough who had initialed certain clauses.

The legal tussle came to light two years ago with the University of Oklahoma arguing that its foundation was the rightful beneficiary of Dr McCullough’s estate. Ms Anthony replaced the university as the plaintiff and has continued the claim, seeking orders that probate for the July 2014 will be granted.

Mr Robinson has instead asked the court to declare the January 2015 will to be Dr McCullough’s final ”testamentary intentions”.

In dispute is Dr McCullough’s estate including the author’s royalties from her 25 books which will accumulate for 70 years after her death. Dr McCullough’s British literary agent, Georgina Capel, estimates the value of revenue streams from the author’s 25 books to be in the “low hundreds of thousands” and likely to dwindle as the years go on. The court heard on Wednesday that the net value of the estate was approximately $1.9 million. It was made up of about $630,000 in cash and parcels of land valued between $1.2 million and $1.3 million.

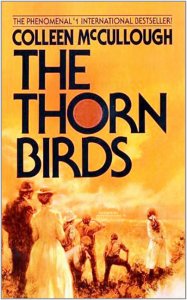

This includes sales from the global bestseller, The Thorn Birds as well as property on Norfolk Island but not the couple’s home which is held in joint names and automatically transferred to her husband after her death.

It sold 33 million copies worldwide, smashed every publishing record at the time, and was turned into an award-winning television miniseries in 1983, starring Richard Chamberlain and Rachel Ward.

It was her seven-novel series on the history of Rome which brought her to the attention of the University of Oklahoma. Dr McCullough was an honorary founding board member of the university’s board of visitors at its College of International Studies. In 1997 she was invited to speak at its first foreign policy conference.

Ms Anthony claims there was no reason why Dr McCullough should change her mind to shun the American university. Further, Dr McCullough did not receive independent legal advice and the making of the document was ”not of her own volition”, she claims.

And, with two wills circulating and claims one is a forgery, the bitter battle over who is the rightful beneficiary and which will is the valid last will of the author is now set to play out in court.

A Last Will & Charity Bequests

A 2008 study reveals that about one in 14 Australians leaves a bequest to charity, but their wish is likely to be over-ruled if relatives contest the will. The survey of 46 major cases by the Brisbane-based Australian Centre for Philanthropy and Nonprofit Studies, found that charities lost the entire bequest in six instances and had it substantially reduced in another 35. “It is difficult to understand why in 2008, an adult of full capacity and understanding cannot choose to leave the entirety of his or her estate to charity, after having provided for any surviving spouse and dependent children,” Centre director Professor Myles McGregor-Lowndes said.

For more information about how to structure your estate planning, or if you have a question about a will, please contact us today. We are specialists in wills and estates, and we offer a FREE 10-minute phone consultation.