Digital death is a thing.

To understand this, think about how much of yourself you have invested in the online realm. Do you have an email address? Social media accounts? Online banking? Do you receive bills electronically? Is your filing done electronically? Where do you keep your passwords? Do your family members know how to access these after your death?

It is estimated that 8,000 Facebook users die each day. But their accounts remain active, which is particularly painful for family members. In October, 2012, 29-year-old British soldier Edward Drummond-Baxter was killed in an insider attack during his first deployment to Afghanistan. But his Facebook page lived on, reviving painful memories for his sister Emily. She says, “If you’ve got someone who’s died, you don’t necessarily want a photo to appear in your news feed saying “Connect with this person” or, you know, “Happy birthday, this person”.”

[Tweet “Have you prepared for your digital death?”]

Emily had to write to Facebook and prove to them that her brother had died. But there was more to Edward’s digital life than Facebook. He bought music, movies and TV shows on iTunes, but Apple wouldn’t transfer ownership of these files to Emily. And when she tried to take over his email account, Google refused to reveal his password for privacy reasons.

Although Edward had died a physical death, it was very difficult for his family to achieve a digital death on his behalf.

Digital Death in Australia

The same difficulty exists in Australia.

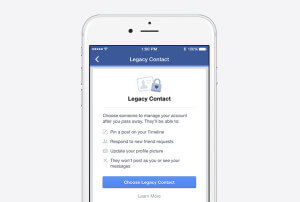

Facebook’s Legacy function.

Some people are now taking matters into their own hands by including in their will a list of passwords for their email, banking and social media accounts, so that the accounts can be dealt with according to their wishes.

But police warn it’s not just about giving family members the ability to deal with your accounts once you have died. Brian Hay from the Queensland Police, Fraud and Cyber Crime squad says a forgotten Facebook page or email account could be hacked and identities stolen.

He says the dead are easy targets. “The reality is you’re more vulnerable because you can’t speak up and say, “Hang on, that new addition to that page is not me. That that information is no longer about me or my family.””

The lack of digital death in this circumstance could be ruinous for the estate or family members.

Some American states have started passing legislation that allows estate executors to access digital files as part of the estate. But it is still largely uncharted territory, with the big tech companies reluctant to co-operate.

[Tweet “Big tech companies can be difficult to negotiate when someone has died.”]

If you want to get your digital affairs in order and prepare for your digital death, here are some tips:

You can take advantage of Google’s “inactive account” service.

The service notifies folks you select that your account has been inactive for a while.

Thereafter, they will be given access to your account for three months.

Microsoft

Your relatives will have to follow a “next of kin” process.

After completing that, account data will be provided on a DVD.

Yahoo and Twitter

Neither of these companies has a set process.

Takeaway: You will have to provide someone with your login information, if you want them to have access to the accounts after you pass away.

You can designate a “legacy contact” who will have some access to your account.

Here is another idea, if all of the above sounds like a hassle.

Consider using an online password manager to store your online account information in one place.

That way, your designated person will be able to assess everything with just the use of a “master” password to open the manager.

As is often the case with estate planning, open communication with your family and legal practitioners is the best course of action. Preparing now will prevent stress for your family members and give you peace of mind – and the sort of digital death you want.

We offer a free, 10-minute phone consultation. Contact us today!